Five Things to Know about Powerful, Adaptive Malware

On Friday, January 19, 2007 the world was introduced to the largest botnet in the world. Those tracking it would soon learn that it was a complex piece of malware that was difficult to address since it had attributes which still impress researchers today.

As Storm spread to as many as 1 million computers, it consumed resources and shut down internet access for hundreds of thousands of people simultaneously, mostly in Europe but a quarter or so in the US. Storm was the most powerful such virus, even having shut down access for the entire nation of Estonia. Where did Storm come from? How was it deployed? What was its motive?

Here are five things you should know about the Storm Worm, one of the Internet's most powerful and adaptive malware.

1. The Storm Worm was a clever, multi-layered attack.

The term “Storm Worm” may be a misnomer, and calling Storm a mere worm trivializes the evil genius behind its creators. Storm combined several kinds of attacks, making it far more sophisticated than the name suggests. First, Storm was a Trojan horse, a kind of malware that presents itself as a benign or mundane action (e.g., a file to download, or an appealing ad to click). Second, Storm is a bot. Malignant bots take hold of a user’s machine and then automate minor actions, often for the purpose of credential stuffing, SPAM campaigns and, when joining a botnet, launching a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack. Thirdly, Storm is a worm, or a kind of self-replicating computer virus that infects a computer, quickly or eventually overburdening it or consuming bandwidth.

Storm combined these elements with many shrewd delivery and operational traits such as restraint in not propagating immediately, dormancy over long periods, distributed command and control (C2), innovation and modification of its social engineering, and counterattacks on sites mentioning it. Moeoever, it is a polymorphic virus, or one whose code includes a mutation engine to alter its signature. As Storm was added to anti-malware databases, anti-malware software failed to recognize it based on the recorded signature. Its new signature would be added in a sort of cat and mouse game, and so on. Specifically, and quite impressive, Storm’s package contained a “polymorphic packer” that enabled it to change its signature every 10 to 30 minutes depending on the version.

2. The Storm Worm affected Windows OS machines, controlling them remotely.

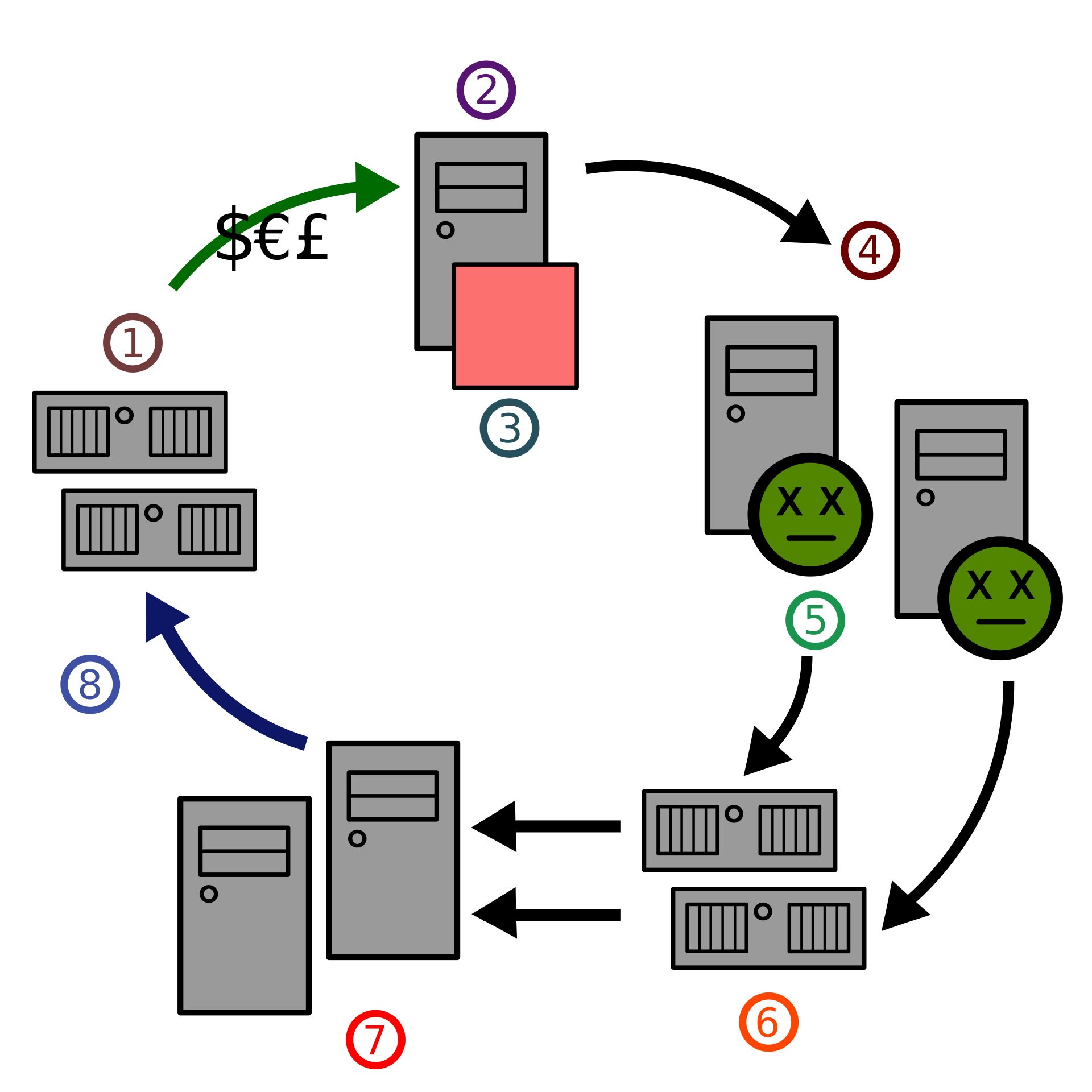

Storm affected an estimated 1 million or more machines in its 2007 heyday, depending on the source. However, Storm only targeted machines running certain versions of Windows. Once downloaded, when a user was duped into clicking a sensational link or attachment, Storm injected a wincom32.sys file that quietly acts as a device service driver. It then creates a group of UDP (User Datagram Protocol) ports. Through them, Storm connects with its encrypted peer-to-peer (P2P) network, established using the Overnet protocol. A period of dormancy might follow. Once activated by its peers, as C2 was distributed among peers on the network, Storm would download a package of .exe files. These had an array of functions including installing backdoors for remote access into the machine, stealing its email addresses, launching SPAM email campaigns to further spread Storm, and launching DDoS attacks.

3. The Storm Worm was deployed using social engineering — lots of it.

“230 dead as storm batters Europe.” This was the subject line of the first SPAM email that Storm sent, enticing people to open it and click an attachment that contained its payload. The Friday, January 19, 2007 launch of Storm was days after Cyclone Kyrill had formed over Newfoundland and just as it was beginning to ravage the European continent, eventually killing 57 people. The cunning methods, though, had just begun. As Storm-infected machines began to take instructions from their C2 counterparts of the P2P network, they began sending emails containing YouTube invites invoking top global celebrity names and ecards from loved ones, all with Storm-infected download links. Subject lines were artful: “dude this is not even on MTV yet”, “awesome new video”, “Cool Video is out” and so forth. The DDoS attack also manifested in the posting of blog-comment spam, luring readers into clicking infected links in threads. When a user whose browser was up to date with the latest security patch was brought to a site with Storm infected links, the following would occur: Storm links were inactive but the page also displayed links such as “click to download software to view your ecard” — a tactic that is very challenging for IT teams to keep up with.

4. The Storm Worm was traced back to Russian hackers, whose motives were profit.

Researchers have concluded that a Russian hacker group in St. Petersburg were behind Storm. The group went or still go by the name Zhelatin Gang aka Storm Gang, or the known cybercrime organization Russian Business Network. Their motive was profit, with usage of the Storm worm acting like a penny stock. Cybercriminals and others with an axe to grind against anti-spam websites and security vendors compensated Storm’s creators to have their adversaries’ information inserted into Storm. In return, Storm launched DDoS attacks on websites such as fraudwatchers.org, 419eater.com, scamfraudalert.com, scam.com, and scamwarners.com. These sites and those of security vendors that target spam and malware were inundated with tons of senseless requests, shutting them down. Storm also acted as a for-rent spam server from which it could host illicit websites or from which untraceable DDoS attacks could be leveraged on any target, since the botnet traffic was decentralized. Tactics such as IP targeting were useless against the decentralized structure and nodes. What was believed to be the world’s largest botnet was a for-hire hosting product on the illicit market.

5. The Storm Worm has been curtailed.

Data as recent as 2016 shows Storm infections to be a few thousands, and not the 1 million or more during the late summer of 2007. Credit goes to Microsoft and security vendors who developed countermeasures such as detection and removal tools for end-users. At the time, law enforcement and others who directed resources toward stopping the worm had a difficult time shutting it down. As Storm C2 was embedded into and distributed among nodes, once a node was shut down it was easily replaced by another, another and so on. Looking through today’s lens, the rules for how to rid a computer of Storm are the same as for any known virus: download antivirus software, scan for known viruses, and follow the instructions to remove it. It is a sound practice to configure an antivirus software’s settings to automatically update so as novel malware is added to the catalogue, you are at pace with the threats out in the wild. Corporate users should be able to rely on their system admins’ capabilities such as detection and removal through device management.

That’s five things you now know about the Storm Worm. To learn more, read the in-depth analysis post on Storm by public-interest technologist Bruce Schneier.